Rhiannon Grant unpacks Barclay’s Apology and explains why we are still talking about it 345 years after it was published.

If you hang around with Quakers for a while, you might hear about a book called Barclay’s Apology. It’s often described as the best, or even only, systematic or academic book on Quaker theology. That’s not the whole story, but it does reflect a special status this book has in the development of Quaker thinking.

What is Barclay’s Apology?

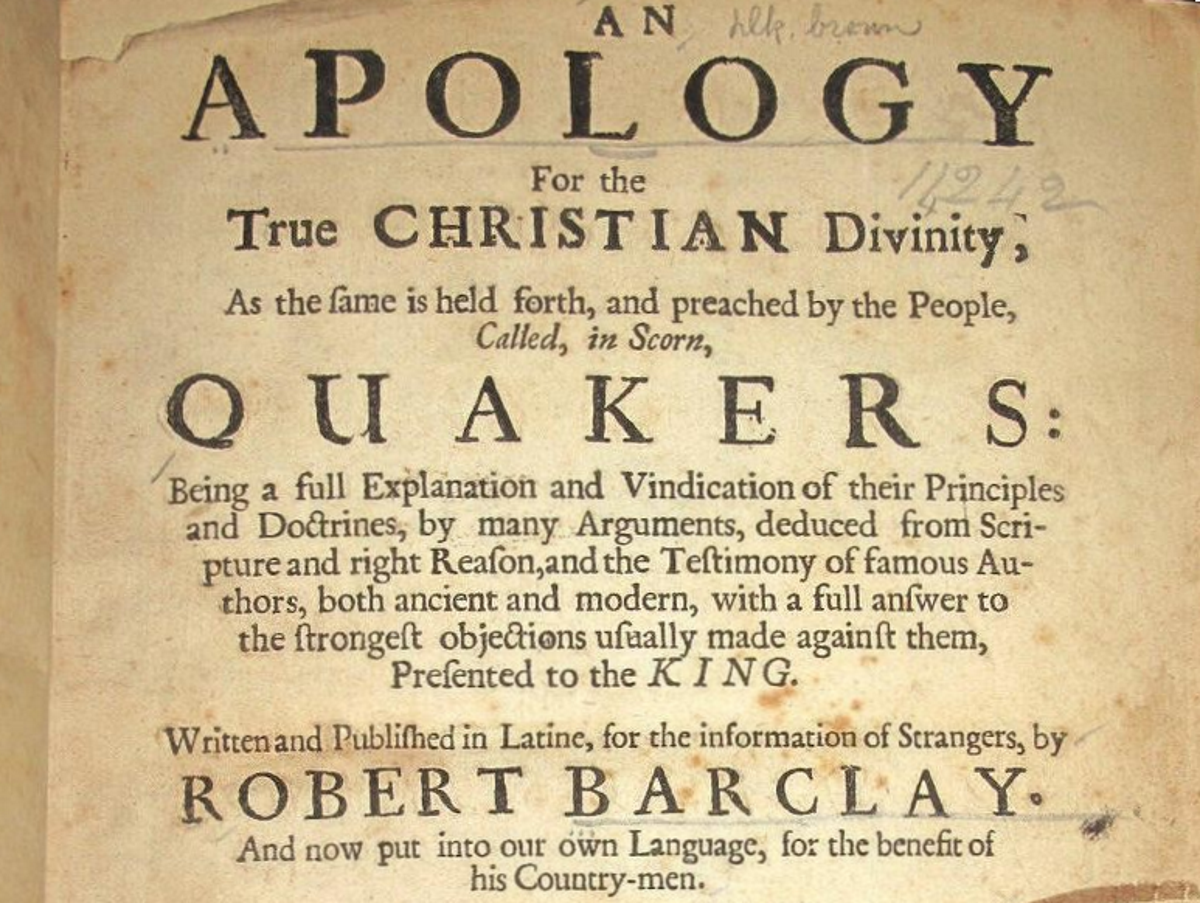

So what is Barclay’s Apology? It’s a book written by Robert Barclay (1648-1690), who trained in formal theology before becoming a Quaker. It’s an apology in the old-fashioned sense of a defence – he’s not saying sorry, but arguing for his position. In the seventeenth century, it was common to give books very long titles (they didn’t worry about soundbites or search engine rankings!) but the first few phrases will give you the idea: it’s An Apology for the true Christian Divinity, as the same is held forth and preached by the people called, in scorn, Quakers. In short, it’s a defence of Quaker belief and practice, which Barclay claims is the best kind of Christian belief and practice.

(Barclay as in Barclay’s Bank? you might be wondering. Yes, distantly – the founders of the bank were descendants of this Robert Barclay.)

What is Barclay’s Apology about? It’s a defence of Quakerism – a series of arguments in support of things Quakers were saying and doing, and being attacked for, at the time. Barclay’s main theme is the importance of the presence of God, in the form of the Spirit or Light of Christ, within all people. He often calls this a seed, something which can be nurtured and grow in us. His evidence comes in two main forms: his own experience of Quaker worship and Christ acting within him, and quotations from the Bible and from other theologians.

Barclay covers questions about a range of theological issues, including:

- Will everyone be saved or only some? Everyone, he thinks, has the chance to be saved, a time of ‘visitation’ when God reaches out, but it’s possible to miss this chance.

- How do we know what God wants us to do? We can listen to God directly, through communion with the inward Christ, and God’s Spirit can also help us read the Bible, which was written by other people who had been inspired by the inward Christ.

- All of them at all times? Yes – Barclay’s Christ is the eternal Christ described in the first chapter of John’s Gospel, as well as the historical Christ who lived and died in first-century Palestine.

- Can we be free of sin while we’re still alive? Barclay thinks we can, but that it’s possible to reach that state, of ‘perfection’, and then fall away from it again.

Barclay’s book is part of a larger conversation which was happening at the time. He responds to arguments he has heard and describes the ways in which he disagrees with other religious groups – Roman Catholic Christians (or as he calls them, Papists), Protestant Christians of various kinds including Calvinists and Lutherans, Jews and (once, very briefly) Muslims all come in for this treatment. Sometimes this seems to contradict other things he says. He thinks everyone can receive God’s guidance, but that a lot of thoughtful religious people are wrong about almost everything. He argues that it’s a sin not to follow your conscience even if you turn out to be factually wrong about something (this is an argument for letting the Quakers do what they want to even if other people find it bizarre!) but doesn’t hesitate to tell other people that they are wrong and should change their practices.

Lots of Quaker published books and pamphlets said these kinds of things, but Barclay was particularly well-educated and went through the questions in an organised way. (Some of the others are more spiritual or personal and less intellectual, and some are more like the kind of yelling at cross-purposes we now see on social media.) That approach and style is one of the reasons this book is still referred to today, although lots of other people have also tried to explain and defend Quaker understandings of theology.

What does it mean to us today?

The Apology isn’t an easy read. The sentences are long and some of the grammar is unfamiliar to English speakers today. A basic background in the Bible is needed to make sense of much of it – although he gives the quotes he relies on, the reader needs to recognise and be able to place names like Paul, John, or Isaiah. Similarly, some idea about Christian history is helpful. You don’t need to know all the details of Origen’s theology, for example, but to understand Barclay you do need to know that Origen was an early Christian writer. Similarly, you need to be able to place Luther and Calvin much later in Christian history, in the context of the Reformation.

However, working through a text like this can be rewarding. Although some questions seem very different in today’s world, there are many points which seem relevant. Like some other early Quaker writers, he gives moving descriptions of meeting for worship and the spiritual effects it can have. He has a knack for vivid images which clarify some theological questions – for example, he compares the Light of Christ within to a medicine and says that we can both have the Light and do bad things, just as someone can have taken a medicine but still be ill. His insistence on the importance of waiting to be led by the Spirit before we speak in worship, teach, or offer other kinds of ministry is still relevant to my Quaker community. And even when I disagree with him, I find it useful to be prompted to think through questions from his perspective.

If you would like to read Barclay for yourself, some versions have been digitised – see the Quaker Heritage Press version or Project Gutenberg. If you would like to explore Quaker theology, but don’t yet feel ready for Barclay, Geoffrey Durham’s book What Do Quakers Believe? and my forthcoming book Hearing the Light are much shorter and more accessible introductions to the key themes. And if you’d like to build up your background knowledge to be ready to read Barclay in future, look out for Woodbrooke courses on Quaker history, theology, and the Bible.