Mark Russ reviews David Gee’s book ‘Hope’s Work: Facing the Future in an age of crises’ and how it makes him reflect on hope and being a Quaker.

I became a Quaker because it gave me hope. In a world not only of uncertainties, but of increasingly likely disasters, the promise that the ‘still small voice’ in the silence of worship can lead us to a better future gave me the hope I was seeking. I have been involved in offering courses on hope for Woodbrooke, and David Gee’s work on hope through his blog https://hopeswork.org/ has been a source of inspiration. So I was delighted to hear of the publication of his book ‘Hope’s Work: Facing the Future in an age of crises’ (2021). Gee has condensed much wisdom into an engaging, compact and very readable book. This book will feed the fire of both those who struggle for a renewed world, and those who are still taking their first tentative steps into the work of hope.

In response to this troubled, seemingly hopeless world of ours, Gee offers a recipe for hopeful living. Each chapter explores a particular ingredient, such as love, freedom, fellowship and faith, but without prescribing any certain outcome: ‘A world in which we knew exactly what was coming over the horizon could not know the word “hope”’ (p.69). He offers no easy answers. Instead of comfortable, reassuring feeling of optimism, we need a ‘conscious hope’ that can survive the terrible things humans do, hope that has been thoroughly ‘disillusioned’. It must be able to face an age of poverty, militarism, and environmental collapse. This real, conscious hope is a tightrope walk, a risky, passionate way of life, ‘a journey of tension, conflict and cost’ (p.28). In the tradition of Joanna Macy and Chris Johnston’s book ‘Active Hope’ (2012), Gee offers a vision of hope as something you do. Because of hope’s dynamic nature, telling stories of hope in action is a crucial part of hope’s work. Hope-filled stories can fill us with hope, particularly the stories of those who have seen humanity at its worst. Gee shares the powerful stories of prisoners, refugees, ex-soldiers and political prisoners, as well as stories from history, fiction and myth.

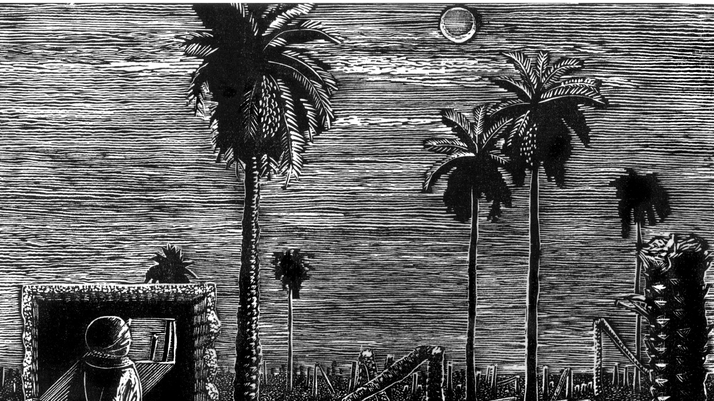

Gee reflects on the 17th century Diggers, a group who emerged at the same time as the Quakers, and reclaimed land for the common good. He speaks of the Diggers as ‘heathens’, meaning not only that they dissented from mainstream religious faith, but that they lived out in the open, were connected to the earth, and challenge the status quo. They were ‘people of the heath’. In what I found to be the most exciting part of the book, Gee proposes that we meet the challenges of the present by harnessing this transgressive, earthy ‘heathen power’. This means getting our hands in the soil and making a deep, long-term commitment to actively loving the creation. Hope springs from this saying ‘yes’ to life, bringing us into fellowship with the whole community of creation. At the same time, hope means saying ‘no’ to lies, to that which denies life, refusing to live untruthful lives, exercising the freedom we have in spite of the consequences.

A strength of this vision of hope, is that Gee makes no appeals to transcendence. The fulcrum of hope, the point of balance between despair and complacency, is acknowledged by Gee to be a mystery. It might be named God or not, it could also be ‘the pull of life’, or ‘the worth and promise of the world’, but David Gee doesn’t dwell on the metaphysics. As a result, this vision of hope, illustrated with stories of people from different religious backgrounds, will resonate with those who don’t identify with a particular faith tradition. This is a hope rooted in the present moment, and chimes with the agnostic universalism common amongst liberal Quakers today. This strength is also its weakness. Gee says that there is no hope for the dead: ‘For what has already been lost, hope arrives too late’ (p.109). Our situation now well may be hopeless: ‘Our ecological crisis… is now believed by many to be beyond hope’s reach’ (p.112). This prompts me to ask, if there is no hope for the past or present, are we just telling stories as the night closes in? Are we attempting to live bearable lives before everything dissolves into meaninglessness? The horrors of past injustice and the terror of future cataclysm still loom over us. Is real hope really possible in such a situation?

Speaking for myself as a Christian, the question for me is, is there anything on the other side of the cross? Gee’s answer appears to be, we just don’t know. I think this is where faith comes in. In his chapter on faith, Gee speaks of steadfastness, of the determination to keep going. I feel faith is more than that, or maybe this is where the boundaries between faith and hope are blurred. On Gee’s blog, he says the word ‘hope’ comes from the Old English ‘hopian’, meaning to trust, or to hold faith. It may come from the word ‘hoffen’, meaning to hop or to leap. It may be that to hope is to make a leap of faith.

I have faith that God is with us in worship, and trust that, to quote Paul of Tarsus, ‘neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation can separate us from the love of God’ (Romans 8:38-39). That means I trust there is something on the other side of the cross. Perhaps Gee is reluctant to speak of transcendence because it tempts us to think that God will sort everything out, leading us back into a comfortable, cosy optimism. This is certainly a trap that many people of faith have fallen into. For myself, I would say that the cross can be the antidote to this temptation. The cross speaks of the costly nature of real, conscious hope. Trusting in resurrection doesn’t release me from the work of taking up the cross, of facing the frighteningly real Golgotha’s in this world, those places of hopelessness where death rules minds and bodies. Ideally, the stories of Jesus’ resurrection should embolden me to take that leap of faith, to hopefully ‘walk with a smile into the dark’ (Quaker faith and practice 29.01).

Hope’s Work: Facing the future in an age of crises by David Gee, is published Darton, Longman and Todd. Hope’s Work is available online from the Quaker Centre Bookshop – the Quaker Centre Bookshop is not affiliated with Woodbrooke but is run by our partners at Quakers in Britain.